Source: MBN from Wikipedia

Save the WTO. It’s not too late. But one day it could be. This global trade body is not functioning today.

I teach Master’s students about the WTO and the gains from trade. I’m doing so this Fall, so I thought I would write you good people a note on the subject. It’s important. What follows is a backgrounder on the institution. Be patient. Not everyone knows the deets about this linchpin institution. In a second post to come later, I will bullet out what I believe is wrong with the WTO and how to fix it.

Background

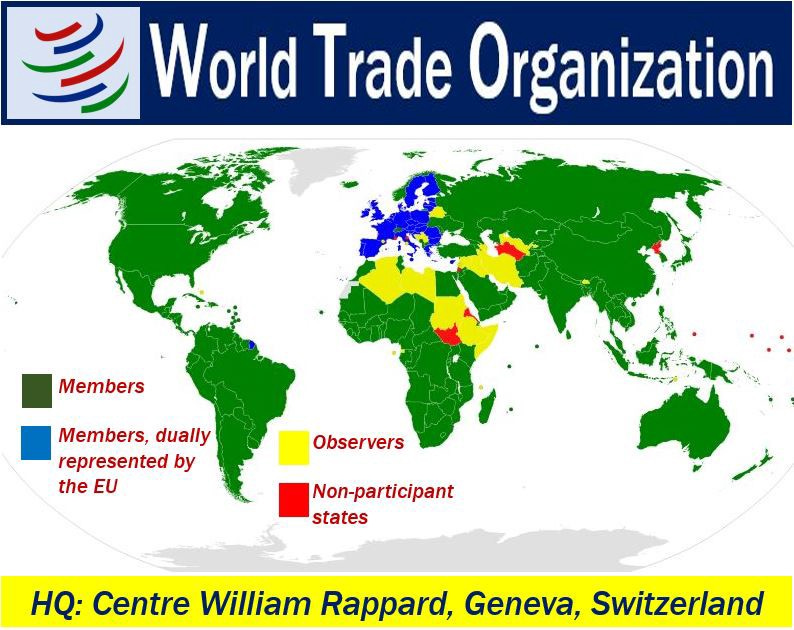

As you can see in the map above, most of the countries of the world are members of the WTO today (164 of them), with another 20+ in the process of joining. That’s nearly the whole world.

Yet right now the World Trade Organization is broken. It cannot perform two of its primary functions — 1) facilitating negotiations among member countries to lower barriers to trade; and, 2) resolving the inevitable trade disputes among members through the Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM).

In 1995, as a result of the world’s last successful global trade negotiation (the Uruguay round) involving 123 member nations, the WTO was launched as the successor organization to the GATT (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade). The GATT had been instrumental in lowering tariffs after 1947. A robust DSM was added to its toolkit in 1995.

Public goods at Bretton Woods

Along with its sister Bretton Woods institutions — the IMF and World Bank — named for the New Hampshire resort where allied countries met in 1944 to plan postwar reconstruction, the GATT was created because, during the Great Depression, trade protectionism, competitive currency devaluations, and the lack of a lender of last resort had ushered in economic collapse.

Underpinning the creation of the GATT was an idea. The idea that trade can be a source of economic growth for all countries, which originated with David Ricardo, a 19th century British economist and Napoleonic-era bond trader. Ricardo came up with the Theory of Comparative Advantage and the gains from trade, which Paul Samuelson, America’s first Nobel laureate in economics, called a “beautiful” idea.

Essentially, all nations can profit from trade by specializing in the export of goods in which they have the lowest costs, specifically the lowest opportunity cost. Opportunity cost is the cost of producing a good in terms of what you give up by not producing other goods. If you specialize in cloth production, in Ricardo’s example, you have to give up wine production. If what you give up is small (because you’re not a great wine producer), then you should specialize in cloth and trade some of it for wine with a country better at making (not necessarily drinking) wine. In Ricardo’s example, Britain has a “comparative advantage” in cloth and Portugal has a “comparative advantage” in wine. So they specialize and trade.

When every country focuses on producing goods in which it has low opportunity costs and trades these, every country’s citizens consume more. If the goal is getting more stuff, then trade is your answer. This view of trade’s benefits is nearly universally accepted by economists.

So, the GATT is based on this idea that open markets make countries better off. Operationally, GATT’s negotiating “rounds” took place every few years and were designed to pry open markets to trade. These rounds, culminating in meetings where trade ministers would sign deals, brought tariffs and other trade barriers way, way down. Trade expanded. So did output.

Due to U.S. opposition, the proposal for a robust DSM was initially discarded. Ceding control to an international body was too much for the world’s new “hegemon”, or leading economic and military power, which had rejected joining the League of Nations not three decades before. Standing athwart the globe after WWII, producing almost a third of world output and possessing a monopoly on atomic weapons, the U.S. could craft the Bretton Woods system to its liking.

The U.S. did cajole other countries to negotiate because trade deals in the GATT required unanimous approval. While pursuing its own interests, the U.S. did not force other countries to agree with all its positions, as the Soviets did on their agenda in their sphere. While the Soviet threat led many countries to cooperate with the U.S., American policymakers would often acquiesce to other countries’ positions because they understood that the viability and longevity of such an institution required members to buy in. The most salient example of this was U.S. acceptance (and encouragement) of the European Common Market (precursor to the EU), which discriminated against American exports.

The benefits of open markets accrued to most of GATT’s membership, as industrial tariffs fell from 40% to 6% today. It is like the richest person in your town selling you on the construction of a new park in the center that s/he agrees to fully fund. Why not? You could ride your bicycle there on Sundays for free, and hopefully your fellow villagers would not be grilling burgers while you did! So you agree.

It’s called a public good, and the U.S. was underwriting three of them on economics at the international level in 1947. Along with the U.N. on security and politics, the U.S. and its allies had created four global institutions. (Not to mention the narrower mutual security organizations that the U.S. led, like NATO.)

One cannot overstate how path-breaking was the insight that U.S. policymakers and their allies had in the 1940s. These new creations — international institutions, which largely did not exist before and which today we are so carelessly undermining — can only last if member countries (and their people) buy in.

Let’s be clear, folks: in an era when it is common to criticize the U.S. (including in these pages), this post-WWII insight regarding international institutions — and America’s pivotal role in supporting them — constitute nothing short of one of humanity’s crowning achievements, unparalleled in history.

Effusive praise, I know. Deserved though.

Sure, these institutions have made mistakes. However, our world has never seen such a broad-based improvement in living standards worldwide, which Bretton Woods bestowed.

So, the WTO is worth saving.

Who gains?

Let’s see now about that assertion in the last section regarding Bretton Woods and living standards.

Bretton Woods has been good for the U.S. (see chart below). Economic growth per person in the U.S. accelerated in the post-war period, beyond what it had averaged during the earlier period of globalization under British hegemony in the 19th century. Institutions such as the WTO helped.

Source: Maddison Project. Sharp decline in real pc GDP growth was due to the Great Depression.

And, it has been good for the world as well (see chart below). US pc GDP growth was strong relative to the rest of the world during the second half of the 20th century, but though remaining robust, fell relative to developing countries in the 2000s, as one would expect when the rest catch up.

Source: Maddison Project. *Decade over decade growth is, for example, growth in 1950 real pc GDP over 1940, and so on, except in 2018, when it is 8 years of growth, i.e. 2018/2010.

It is true that many developing countries benefitted less than advanced economies from trade liberalization, because many of them exported agricultural goods, which the U.S., Europe and Japan refused to liberalize for many years. No free trade for Argentina, folks. Perhaps we can understand a bit then why that country, as well as others, has not fully bought in to the U.S.-led system. Those developing countries that did industrialize — Korea and China come to mind — benefitted handsomely.

As WTO membership grew and U.S. relative power waned, developing countries grew more assertive. Given the unanimity requirement in the GATT/WTO, deals suddenly became out of reach. The last negotiating round, the Doha round, begun in 2001, has failed.

No new deals in a quarter century, friends. Looks like we have a working definition of a failing institution.

The issues raised in the Doha round were complex and controversial. They dealt not simply with reducing industrial tariffs, but with agriculture, services, IP protections, investment rules, state subsidies, government procurement, anti-trust, and the environment. Getting 164 trade ministers to agree on such topics — let alone presidents, prime ministers and potentates, not to mention legislatures — is more than you can ask from diplomacy.

Alphabet soup

Smaller agreements in the WTO have been reached on trade facilitation (simplifying customs processes) and IT, some of them only including a subset of members (so-called plurilateral deals). Plurilateral negotiations are ongoing in services trade and government procurement as well.

And, importantly, regional trade deals involving a smaller group of nations, occurring outside the GATT/WTO, such as the EU and NAFTA/USMCA, as well as many bilateral agreements, have flourished. More recently, however, TPP and TTIP (the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, mega-regional deals between the U.S. and Asia-Pacific and the U.S. and Europe, respectively) have floundered due to an angry U.S. — personified in the anti-trade, anti-globalization campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump circa 2015–2020.

This alphabet soup of trade deals — by establishing rules among likeminded countries on important issues such as state subsidies and IP protections — are worth resuscitating. The idea here that Barack Obama pushed hard in TPP is that China, the world’s second largest economy, accused of cheating by subsidizing its industries and appropriating IP, would ultimately agree to follow international norms. The thinking is that China would ask to join TPP in order to access markets. To join, they would have to comply. Instead, thanks to Bernie and Trump, the U.S. has pulled out. And, China has offered Asia an alternative on its own terms called RCEP, which many countries have accepted. Meanwhile, the EU just signed a free trade deal with Japan.

Can I ride for free?

Free-riders are a problem for public goods such as the WTO. It’s what political scientists call the compliance problem. An individual country does not have to comply with agreed-on tariff reductions, but can still benefit by exporting to other countries who have lowered their tariffs. Likewise, governments can subsidize their companies so they can underprice foreign competitors.

Free-riders undermine the system. Why should I open my markets if country X is not opening theirs? This thinking caused the breakdown in global trade during the Great Depression.

Such behavior is why you need a hegemon like the U.S. (or Britain in the 19th century) cajoling countries to behave. And, why the relative decline of the U.S. is problematic.

But, some political scientists have argued that eventually credible institutions of globalization can take on a life of their own, independent of a hegemonic sponsor. Acceptance of the rules becomes so widespread that institutions like the WTO remain robust. Not happening now. Major efforts by world leaders of good will are required (subject of the next post).

So, absent hegemonic support, a functioning Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM) is vital to WTO relevance. When the DSM works and a country breaks the rules, DSM adjudicators rule that this country must start following the rules. If the country refuses, then the country that initiated the complaint can raise tariffs against the offender. A working DSM ensures buy-in from those who follow the rules and could make the WTO self-perpetuating.

The Ballad of Barack, Donald, Lighthizer, Joe and Katherine, John and Yoko, and the WTO Appellate Body, available today on Spotify…

Since Dec. 2019, dispute settlement no longer works. The U.S. under Donald Trump refused to approve adjudicators to the Appellate Body of the DSM, rendering the issuance of binding judgments by the WTO impossible. Since the days of W, the U.S. has objected to the “overreach” of WTO rules by appellate judges.

Barack Obama rejected appellate judges, which shocked trade experts back then. Yet he ultimately allowed the Appellate Body to become fully staffed again. He sent a message to trading partners on overreach without wrecking the institution.

Trump wrecked the institution. In fact, his WTO-skeptic Trade Rep., Robert Lighthizer, famously threatened his fellow trade ministers in a speech in Buenos Aires in 2017, as Doha was on life support, that the U.S. would kill the DSM. Within two years, the protectionist duo allowed the seven-member Appellate Body to fall to only one judge, when a minimum of three is required.

Trump and Lighthizer effectively “shot the sheriffs”, to quote an excellent Peterson Institute of International Economics (PIIE) article on the topic (and of course, Bob Marley). Today, any country brought to the DSM with a complaint against it for unfair trade practices can appeal to a body that no longer has staff.

Biden, promising a new beginning (remember: “America is back”) and his new Trade Rep. Katherine Tai, while approving the appointment of a new Director General of the WTO (see below), a post Trump had left vacant for six months, has not moved to approve new adjudicators. I guess America is not “back” on trade. It should be, but trade liberalization has never been good politics, neither for Democrats nor Republicans. First terms are notoriously protectionist.

The doctor is in…

Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala is the Director General of the WTO, and was formerly Finance Minister of Nigeria and for a quarter-century an economist at the World Bank, rising to #2, the MD for Operations. She was also instrumental in 2020 in the global fight against COVID-19. See her bio here. The WTO was left leaderless for six months by the resignation of DG Roberto Azevedo who decided instead to join PepsiCo. Ok, from global rules to sustain economic cooperation to junk food. To each his/her own. After Azevedo’s resignation in Aug. 2020, the Trump administration wouldn’t back the consensus candidate (Dr. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala), who was approved within a month of Biden taking office. The WTO DG has little executive power, given that power is vested in member countries. Source: WTO

But America once loved the DSM…

Ironically, the U.S. has been the largest user of the DSM since its inception. Of the more than 500 complaints made to the DSM, the U.S. lodged 124 of them and was on the receiving end of 156 complaints. By contrast, the EU had lodged 97 complaints and received 84, while China had lodged 15 and was the subject of 39 complaints through 2017.

As countries like Japan, Germany and Korea, and later China, have industrialized, their export penetration of the U.S. has increased, hurting specific sectors (e.g. textiles, autos, electronics), as well as workers in these sectors and related localities. Trade, like all economic activity, creates winners and losers, in spite of the fact that the U.S. overall has experienced sizable gains from trade and from trade agreements.

Anger emerges in sectors affected by foreign competition and is channeled through Congress and the campaign trail. The best answer to this challenge includes adjustment assistance and training for those losing jobs. Unfortunately, that is the stuff of policy wonks and newsletters, while demonization of China and other countries may play better in Peoria or Pennsylvania...or New York.

Before the advent of the DSM in 1995, the U.S. vented its anger by engaging in aggressive bilateralism against competitors, which Trump has reprised. It imposed “voluntary export restraints” (VERs) on countries such as Japan and Korea, covering as much as 12% of U.S. imports by the mid-1980s.

The US also implemented “trade remedies”, effectively raising tariffs against imports. Trade remedies are allowed under WTO rules, another reason why DSM rulings are critical. If imports are surging, being subsidized, or are unfairly priced, trade remedies can be imposed.

Trouble is, prior to the DSM, the U.S. itself decided when trade remedies were appropriate, through the International Trade Commission in the Department of Commerce. As a result, trade remedies rose to as high as 5.5% of imports in 1999.

The U.S. still possesses this professional, transparent, formal process of assessing injury to American firms from trade within Commerce; however, with the DSM, the U.S. has had to follow WTO rules and DSM rulings.

A miscalculation

The U.S. made a compromise with other members as part of the agreement to form the WTO in 1995. America’s trading partners wanted the U.S. to stop using VERs and to curtail trade remedies. The U.S. agreed to do this in exchange for a robust DSM and other positive actions (including on IP protections and services).

This was a miscalculation.

The U.S. had expected the DSM to help it pry open other countries’ markets, while giving the U.S. a free hand on trade remedies. On the contrary, nearly two-thirds of the complaints against the U.S. reaching the DSM have been about trade remedies. And, not all the rulings have been in America’s favor.

The U.S. wants freedom of action on trade remedies. A hegemon in relative decline having its freedom curtailed by foreign judges? How dare they! We created Bretton Woods!

True, America’s competitors have unfairly subsidized their exporters. But, the U.S. has also subsidized exporters, notably in defense-related hi-tech and agriculture. So, no holier-than-thou rants, please…

So, when the DSM rules against U.S. trade remedies, the U.S. cries, “overreach”, a criticism that may at times be justified.

Muscular multilateralism

President Obama utilized the multilateral machinery in a muscular fashion, especially vis-à-vis China. His administration initiated 25 complaints with the DSM, more than any other country during his administration, 16 of which were against China. Of the latter, the U.S. won 7 cases — on subsidies of aircraft and agriculture, as well as duties on steel — with other cases pending.

Muscular multilateralism is the only viable way forward for the U.S. A temper tantrum on the world stage tipo Trump is not effective. WTO reform is necessary, and the Biden administration should sit down soon with the EU and other likeminded nations like Japan to hammer out a deal.

In fact, the EU issued a report in February setting out their priorities and tipping their hat that they sympathize with U.S. concerns, notably on DSM overreach. But dismantling the DSM completely, or going back to the GATT which the U.S. dominated for decades, perhaps one of Robert Lighthizer’s nightly bedtime dreams, is not an option for adults.

Watch this box for Part 2 on the WTO, which will bullet out how to fix this indispensable institution.